In 1998, I visited Washington, D.C., for the first time with my wife, Mary Anne and daughter Sarah. We visited as many museums as we could, using the hop-on-and-hop-off trolleys. Sarah was 13 at the time, and we felt she would be able to handle the United States Holocaust Memorial and Museum. After all, the Holocaust wasn’t new to Sarah since both my parents were survivors. It was a solemn day, but I can’t say it was overly emotional.

Fast-forward to 2024. My memoir was to be released, and I had begun work on a new book about intergenerational trauma. I decided it was the right time to return to Washington and see the Holocaust museum again.

Mary Anne and I planned a trip so that we would also meet up with two friends who were also writers, Ellie and Karen, and all go to the museum together. I really had no trepidation about the visit. I had been before, and as a volunteer docent at the Toronto Holocaust Museum, I was comfortable with the subject matter.

I was so wrong.

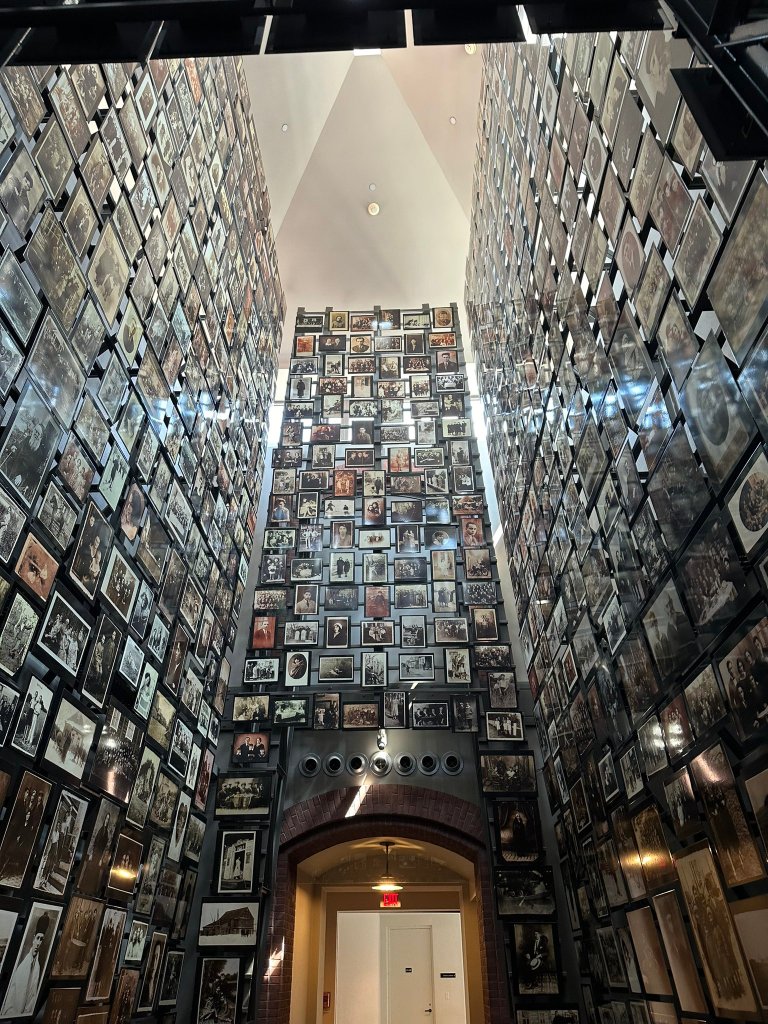

After clearing security, we travelled to the start of the permanent exhibit by elevator. As the metal door clanged shut on the gray-walled car, I was startled, and images appeared in my head. I imagined the metal doors of a gas chamber trapping us. It went downhill from there. Nothing in the exhibits was new to me. I had seen it all before. I had written about it. But in this place, I was being pulled into every photo and artifact. I was the boy begging in the streets of the Warsaw Ghetto. That was my father dragging heavy paving stones. My mother was being assaulted by Nazi thugs. I was in my own personal hell.

Why did I think this was a good idea? I was light-headed and clammy. I felt nauseous and several times I felt that I was going to throw up. I staggered into a washroom to splash cold water on my face. It didn’t make a difference. I wanted to bolt from the building. I could feel the eyes of others in our group looking over at me. I had no reason to be here. I had nothing to learn or prove.

When I reached the boxcar on display, I stepped inside. I was the only one standing in there, but it felt claustrophobic, and I could barely breathe. It was smaller than I had pictured. I couldn’t visualize it holding 60 or more people. Every member of my family had travelled in one of these cars – some survived, and some perished after arriving at their final destination. Typically, they travelled for several days without food or water in stifling heat or frigid weather. The heaviness of this place was crushing.

I finally left and found a brightly lit spot to sit down and clear my head. With my head in my hands, I wept, not because of sadness but because I’ve been through all that over the past few years. It was out of frustration. To this day, I cannot understand why it happened. Why did people go along with it? Why did no one try to stop it? How can people live with themselves after intentionally killing babies? I have so many questions, but there are no answers.

All I can do is tell my family’s story over and over again, usually to a sympathetic audience. But if I can reach even one person who doesn’t know or wasn’t aware, I have accomplished something and honoured my family.

I finally got up and walked to the Hall of Remembrance – a hexagonal structure used for public ceremonies and personal reflection. Inscribed on the walls are some of the names of concentration and death camps. I lit candles that were available and said Kaddish (Mourner’s Prayer) for my lost family.

Why would this museum cause me so much anxiety when I regularly visit our local museum? The Toronto Holocaust Museum is a wonderful facility, but it was designed more as a teaching centre than a museum. Thousands of students go through the facility to learn, hopefully not be traumatized. That was done intentionally.

I will never return to the Washington Museum. There is no reason to return. The facility isn’t for descendants of Holocaust survivors. We know too well what happened. The stories return to us at night or during stressful times. We are reminded during holidays and family get-togethers because there are so few of us to celebrate. One day, I will wrestle free from the trauma that haunts me. But I will be able to forget what happened.